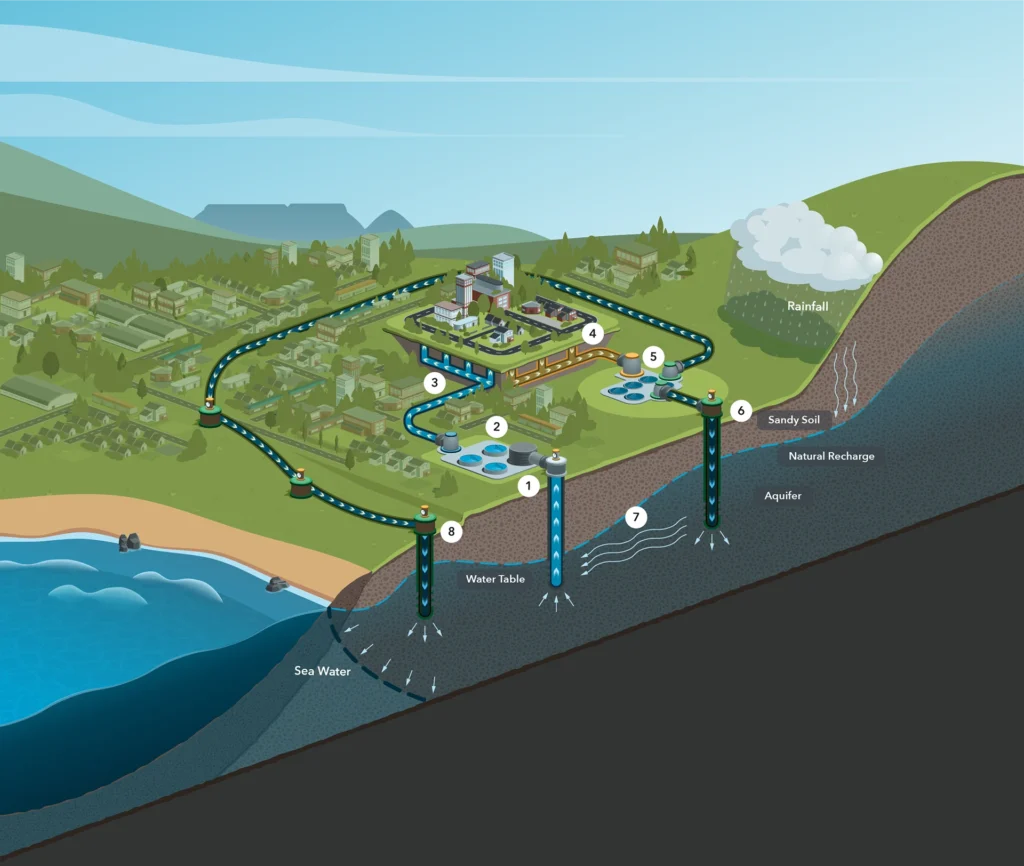

Groundwater is now the world’s most heavily extracted source of freshwater, supporting drinking supplies, irrigation, industry, and ecosystems across every continent. Yet the very systems that store and move this water—aquifers—remain poorly understood in many regions, which means societies are often “flying blind” when making decisions about pumping, cropping patterns, and infrastructure. As climate variability intensifies and water demand grows, understanding aquifer characteristics is no longer optional; it is the foundation of any credible groundwater sustainability strategy. When communities do not know how their aquifer behaves, decisions about pumping, crop choices, and recharge become guesswork. This blog explains why understanding aquifer characteristics matters, how such knowledge can guide sustainability planning, and how it can shape real actions on the ground, especially crop planning.

Why aquifer characteristics matter

Aquifers are underground layers of rock or sediment that hold and transmit water. But they are not all the same. Some store large volumes and recharge quickly; others hold little water and refill very slowly.

These differences influence:

- How much water is available, and for how long.

- How fast water moves, which affects how wells recover.

- How quickly an aquifer recharges after pumping or rainfall.

- Water quality constraints, including salinity or contaminants.

These differences matter because they set the sustainable limits of use. When pumping exceeds what an aquifer can replenish, the results include long-term water-level decline, land subsidence, streamflow reduction, and, in coastal or island settings, saltwater intrusion that can permanently degrade the resource. Understanding whether a particular aquifer refills in seasons, decades, or centuries is therefore central to deciding how much water can be used without undermining future supplies.

Aquifers behave differently — and so must our management strategies

Some aquifers store water in large, porous sediments; others rely on narrow fractures in hard rock, and recharge rates can vary from rapid to extremely slow. Without identifying these differences, groundwater management becomes guesswork and can lead to rules that are either overly restrictive or dangerously permissive.

Flow patterns determine resilience

Understanding how groundwater moves tells us how fast wells recover after pumping, how far contaminants can travel, where recharge actually reaches, and how groundwater interacts with rivers and wetlands. Flow is effectively the “heartbeat” of an aquifer, and ignoring it leads to unintended consequences such as rapidly declining water tables, drying streams, or failing recharge structures that never reach the target aquifer.

Storage capacity defines sustainable limits

Storage capacity defines how much “buffer” an aquifer provides and thus how much can be withdrawn in droughts versus normal years . Regions with limited storage cannot support deep pumping or water-intensive crops without risking long-term decline, while areas with higher storage can support more productive agriculture only when withdrawals remain aligned with recharge. This distinction helps planners separate renewable groundwater use, where pumping roughly equals recharge from deliberate groundwater mining, which might be

acceptable only as a short-term, planned strategy.

What We Need to Do: Building Aquifer Understanding

- Map and Characterize Aquifers

Mapping reveals where aquifers are, how thick they are, and where recharge occurs. This helps identify which areas are naturally water-rich and which need protection. - Monitor Groundwater Levels Regularly

Tracking water levels over seasons and years helps distinguish between temporary declines due to drought and long-term depletion. - Link Aquifer Science With Policy and Local Planning

Aquifer knowledge is useful only when it shapes decisions such as limits on pumping, incentives for efficient irrigation, or placement of recharge structures. - Build Community Awareness

Farmers and local water users make daily decisions that influence groundwater. When they understand how aquifers behave, they can make more sustainable choices.

Translating Aquifer Knowledge Into Crop Planning

One of the most powerful ways to use aquifer understanding is to align crop choices and irrigation practices with the aquifer’s ability to supply water.

Peer-reviewed studies show how aquifer science can guide more sustainable agriculture:

- Aligning crop water demand with aquifer yield: In low-storage or slow-recharging aquifers, research shows that shifting to crops with lower water needs helps stabilize groundwater levels and reduces risk for farmers.

- Adjusting crop area: Studies have demonstrated that reducing the area under high water crops like rice or sugarcane can bring groundwater extraction closer to sustainable limits.

- Improving timing of planting: Groundwater modelling has shown that matching crop calendars with periods of better recharge reduces stress on overdrawn aquifers.

- Incorporating water quality: Where salinity or contaminants are present, researchers recommend using salt-tolerant crops in affected zones and reserving good-quality groundwater for drinking and sensitive crops.

These studies highlight that crop planning must respond to aquifer behaviour—not just market

demand.

Examples of Aquifer-Based Crop Planning in Practice

Several real-world programs have used aquifer understanding to guide crop choices and improve water sustainability:

Atal Bhujal Yojana (India): Communities use aquifer maps and groundwater budgets to adjust cropping patterns reducing summer paddy and sugarcane in low-yield aquifers and promoting millets, pulses, and horticulture.

Andhra Pradesh Farmer Managed Groundwater Systems (APFAMGS): Farmers track groundwater levels and adjust crop choices based on aquifer storage, leading to shifts toward less water-intensive crops during low-recharge years.

Maharashtra GSDA Aquifer-Based Pilots: District teams use aquifer maps to advise farmers on changing sowing windows and reducing irrigated area in hard-rock aquifers.

Cuauhtémoc Aquifer Plan (Mexico): Aquifer models informed cropping adjustments reducing water-intensive orchards and expanding lower-water forage crops.

These examples show that when aquifer science is paired with community engagement and policy support, it leads to practical, sustainable change.

Designing effective recharge structures

Aquifer properties determine where recharge structures will work, how deep they should be, and whether infiltration basins, check dams, or recharge wells are appropriate. Without

matching structure design to permeability, depth to water table, and flow paths, recharge efforts often fail or deliver minimal benefit because water never reaches the intended aquifer or bypasses key storage zones.

Regulating pumping based on flow and recovery

If flow is slow or recovery is limited, regulations may need to impose spacing limits between wells, cap extraction during dry months, or set maximum allowable drawdown to prevent interference between neighbouring users. In faster-recharging or more permeable aquifers, rules can be more flexible but must still guard against cumulative declines and ecological impacts, especially where groundwater supports baseflow and wetlands.

Guiding energy and irrigation policies

Energy subsidies, irrigation schedules, and pump efficiency programs should be linked to aquifer health, so that areas with declining water tables face stronger incentives for conservation and efficiency. For example, where water levels are falling, reducing or restructuring electricity subsidies for pumping and promoting high-efficiency irrigation systems can slow depletion and control rising energy costs. In aquifers that remain within sustainable

limits, policies can focus on maintaining efficiency while supporting productive use and robust monitoring.

Protecting groundwater-dependent ecosystems

Aquifers connected to rivers, wetlands, or springs need extraction limits that maintain environmental flows and water levels in these groundwater-dependent ecosystems.

Understanding connectivity ensures ecosystems are not unintentionally starved of water, helping safeguard biodiversity, cultural values, and services such as filtration, habitat, and recreation.

Sustainability starts below the surface

Groundwater sustainability does not start with pumps, pipes, or even laws; it starts with the aquifer itself. When societies understand how their aquifers store, move, and replenish water, they can design crop systems, energy regimes, allocation rules, and recharge investments that work with the resource rather than against it. Aquifers are long-lived natural assets, and protecting them requires first seeing them clearly, then embedding that understanding into every decision that affects water, food, and energy. Understanding aquifers is not a one-time

task. It requires ongoing monitoring and regular updates to management plans.

When communities know their aquifer’s limits and behaviour, they can:

- Choose crops that match water availability.

- Use irrigation more efficiently.

- Support policies that protect the resource.

- Invest in recharge where it will actually work.

Groundwater sustainability starts below the surface with the aquifer itself.